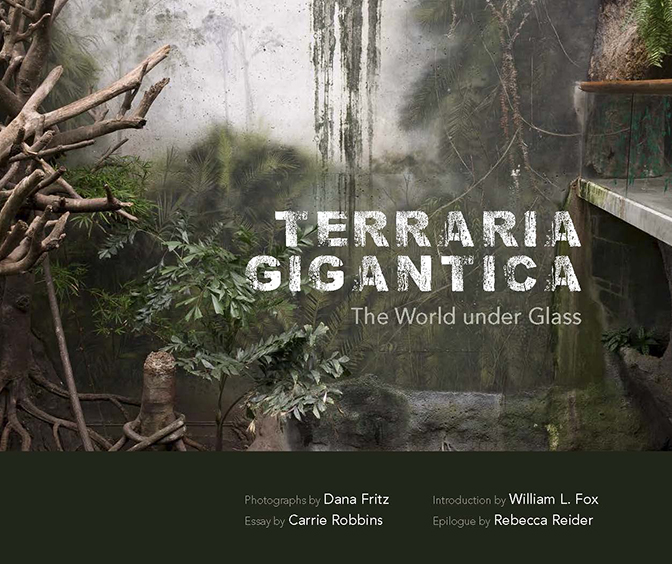

Recently published, Terraria Gigantica: The World under Glass by Dana Fritz explores the itersection of natural and controlled environments through a series of photographs made in some of the world’s largest enclosed landscapes. Recently, the COMP Magazine caught up with Fritz while she was in Chicago at a book signing at the Museum of Contemporary Photography to discuss this publication, her approach to color vs. black-and-white photography, what she values most in her aesthetic practice, and how she shares these experiences with her students at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Dana Fritz, Pond, Lied Jungle, archival pigment print

Meeting you and securing your book, Terraria Gigantica: The World under Glass, at the Museum of Contemporary Photography Chicago’s recent book signing was a most pleasant surprise. Perhaps, we can start with a little background. You are Professor in the School of Art, Art History & Design at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and investigate the ways we shape and represent the natural world in cultivated and constructed landscapes. I am wondering if there are any early or specific items or people who piqued your interest in this aesthetic pursuit?

I often say in my lectures that I grew up in a post-World War II suburb of Kansas City called Prairie Village. Our house was on a tree-lined street that was part of the grid. There was no prairie anywhere nearby and I spent my outdoor time in my own yard, in the schoolyard, or the park a few blocks away. When not at home in Prairie Village, my experience of nature was limited to girl scout camping trips, occasional family vacations to National Parks, and visiting my grandparents’ farms in Missouri. My idea of nature was always in the context of a park, camp, or farm- each with their own degree of visible human intervention and each bounded or framed like a view from a window. As an undergraduate student, I began to look more deeply into gardens, natural cycles, and native landscapes of the Midwest and west, including the prairie. I have been working with these or related subjects for over twenty-five years.

Dana Fritz, Terraria Gigantica: The World Under Glass, book cover, 2017

In “Terraria Gigantica: The World under Glass”, (2017), I am reminded of early photography practitioner’s interest in the cross-section of art and science. Specifically, I see this work as approaching content in a format that is partly about aesthetics while simultaneously commenting upon scientific methods. I’m wondering if you can comment upon your approach in this investigation? Are there any specific findings you hoped to convey to the viewer?

I don’t have a background in science at all but I have a strong interest in a basic understanding of ecosystems- why certain plants grow here and not there, who eats them, how they shaped various cultures, etc. I was originally drawn to the large vivaria in Terraria Gigantica because of my fascination with the idea of creating and containing a landscape or biome and the inherent combination of natural and artificial elements therein. Because of these juxtapositions and the missions of these places, the constructed biomes are visually striking and designed to create a sense of awe for visitors. As an artist, I find them strange and beautiful and worthy of contemplation as symbols of our relationship with the natural world. Inside them, it is often impossible to discern natural from artificial. Michiel Schwarz wrote that the most important question now is not what is or is not nature, but “what kind of nature do we want?” I think these places are tools to help us understand the wider world but I wonder if they are a substitute for time outside for many people. I have grown to deeply appreciate the work they are doing in a number of areas including endangered species propagation, climate change research, and environmental education. The Henry Doorly Zoo, Biosphere 2, and the Eden Project all promote science literacy, something that seems to need extra support these days.

Dana Fritz, Corner Outlet, Lied Jungle, archival pigment print

In “Views Removed” and “Garden Views” you work in black-and-white. These projects consist of formally beautiful and contemplative images of natural environments and organized gardens. When approaching this work versus the color imagery found in the noted book, are there any different ideas or techniques you consider when making these photographs?

The biggest difference is that the black and white work is all shot on film and printed in the darkroom. I still really enjoy that process and prefer it to spending my studio time on the computer since I use a computer for so many other parts of my life. I think of all of the projects as conceptually linked: they are all about “the imagined landscape” whether a formal garden, a vivarium, or an invented landscape constructed by me from multiple negatives in the darkroom. The methods of working in Garden Views and Terraria Gigantica are essentially the same: making “straight”, descriptive photographs of carefully designed places and printing them without much manipulation. Views Removed was the most challenging because, at first, I didn’t know how or even if I could figure out a way to get the white background and equivocal space I was after. I shot those in “parts”, often not knowing which ones I would use together. The prints require a lot of thinking ahead: flat lighting with no shadows, a white sky/background, over-developing the film, lots of dodging/burning/masking and bleaching the prints, etc.

Dana Fritz, Zig Zag Bridge, Okayama Korakuen, silver gelatin print

At this point in your career, what do you value most in your aesthetic process?

This seems like a luxurious question! Looking back, I realized that I had structured my earlier work around more predictable outcomes because funding for it was based on successful grant writing that privileges measurable outcomes over open-ended exploration. Of course, I discovered many things along the way, but my goals were more tangible. After I was promoted to full Professor, I felt liberated to try something more exploratory, that I could not fully describe, and for which the outcomes were unknown. That’s when I began to work on Views Removed. I value my experience in working both ways and that I have the freedom and support to pursue my intellectual inquiry as an artist wherever it takes me.

Dana Fritz, Japanese Black Pine Glacier, silver gelatin print

You teach photography at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. I assume that this is a big part of your life. In the classroom (and beyond), I am curious if there are any specific thoughts or practices you regularly share with your students? What do you find most rewarding in the process of teaching?

Being on the faculty at UNL is indeed a huge part of my life and my identity and I can’t imagine a job more suited for me than the one I have. I hope to serve as a model for my students in my studio practice, intellectual inquiry, and my professional involvement in our local, national, and international art communities. Larry Gawel and I have been organizing photography exhibitions at Workspace Gallery in Lincoln for almost ten years and many of the artists come to Lincoln and interact with students. This work certainly connects our local art community to national and even international artists. There are so many aspects of teaching that are rewarding: from print-viewing at the Sheldon Museum of Art on campus, to engaging in lively reading discussions, to watching students make beautiful silver prints, to witnessing powerful student-led critiques, to mentoring graduate students, to leading a short-term study abroad course in Japan, to helping students “find” their work and grow in it, to hearing students tell me about an artist/book/exhibition that they are excited about, to seeing student successes during school and after graduation, and so much more. While there are plenty of challenges, these things remind me why I love teaching.

Dana Fritz, Matsushima 1, silver gelatin print

2018 appears to be rather full at outset. You are presenting work or doing an artist lecture at a number of sites, including the Lux Center for the Arts, Lincoln, Bryn Mawr College, the Duluth Art Institute, and the University of New Mexico Art Museum. You appear to be in a great place in your career. Do you have any additional materials or exhibitions in the works? What’s the plan for the remainder of the New Year?

Yes, 2018 does seem quite full! There will likely be a few more exhibitions scheduled and I will continue to promote my book while it is still relatively new including at the Tucson Festival of Books in March. I will lead another study abroad course to Japan in May and stay afterward to photograph and research. I am looking into artist residencies for the coming years and have started a very open-ended project in the Nebraska National Forest, once the world’s largest hand-planted forest and an experiment in localized climate change. While it is a new site, many of the ideas carry over from my other projects.

Bamboo and Snow, Tenryu-ji, gelatin silver print

For additional information on the work of Dana Fritz, please visit:

Dana Fritz – http://www.danafritz.com/

Dana Fritz on Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/danafritzphotography/

Dana Fritz Instagram – https://www.instagram.com/danafritzphoto/

Workspace Gallery https://sites.google.com/site/workspacegallery/home

University of Nebraska-Lincoln Photo https://arts.unl.edu/art/photography

Terraria Gigantica: The World under Glass – https://www.amazon.com/Terraria-Gigantica-World-under-Glass/dp/082635873X

Additional images from Terraria Gigantica: The World under Glass by Dana Fritz:

Dana Fritz, Banana Conveyor, Eden Project, archival pigment print

Dana Fritz, Green Ductwork, Eden Project, Archival Pigment Print

Artist’s interview by Chester Alamo-Costello