One of the pleasures of visiting artist’s studios in Chicago for the better part of 30 years is the ability to see how artists explore and work with a wide range of mediums and techniques. There have been new digital and sculptural technology introductions. There have been those who’ve reclaimed and utilised abandoned materials found in dumpsters. And, there have been those who’ve preserved (and advanced) long practiced, often overlooked, painting techniques, to name a few. Steven Carrelli is the latter. I first encountered Carrelli’s hyperrealist paintings at the Wood Street Gallery in the mid-to-late 1990s. I have long wanted to visit his studio. This week the COMP Magazine took the Red Line up to Rogers Park to discuss his passion for traditional painting practices, his ongoing investigation into optics and theories of seeing, how his work has shifted and transformed over time, and how he shares his studio practice with his students.

You have been creating serious work in Chicago since the mid 1990s. I am wondering if we can step back a bit and discuss your early introduction to the visual arts? Can you share with us any specific events or people who may have had an impact in piquing your interest in painting?

I was not raised around art or artists (I grew up in an Italian Immigrant family in the working-class environment of Canton, Ohio), but my high school had a great theater program, so I got interested in theater pretty young. In college, I got interested in the visual aspect of theater – stage and lighting design, technical theater, and fabrication – and I thought it would be a good idea to take some art classes. I took an art history course on 17th-century Dutch art, and I really loved studying that. I took a beginning drawing class, which really intimidated me, because I didn’t have any art experience, but I worked like crazy at drawing. Those experiences introduced me to the possibility that art could be a serious course of study for me. Eventually, I realized that I was dropping classes in my declared major (which had shifted a couple of times over the first two years of college, until I had declared myself a psychology major) in order to spend more time on my paintings, and I knew that I needed to take this seriously. Joel Sheesley was my painting professor at Wheaton, and he gave me some of the best advice I’ve ever received as a young artist. He told me that, if I were going to change my major to art, I should commit to working rigorously above and beyond mere assignments. That idea that art is labor came to mean a lot to me, and it made the work of artmaking accessible to me. After college and before graduate school, I met Tim Lowly, who became a real mentor to me as a painter, and he subsequently became one of my dearest friends. I was trying to figure out what painting meant to me and how to go about making serious work, and Tim’s work and artistic practice impressed me because it was intensely intertwined with his most deeply-held values and it was utterly unpretentious. He led me to think about how humane art can be at its best. I still carry those lessons with me.

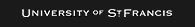

egg tempera and oil on panel, 21” x 11 ¾”,

Collection of the Illinois State Museum, Springfield, IL.

I see a strong affinity and interest with traditional painting practices. Specifically, you often work with egg tempera? This medium can be traced back to ancient times. Egg tempera was used in the ancient world, an excellent example is the Fayum mummy portraits, produced in Egypt between the 1st century BC to the 3rd century AD. Can you discuss thoughts on the technical aspects of your practice? Why do you see this medium holding such longevity?

You’re right, I do love traditional materials and practices, and egg tempera is particularly important to me. I find that the repetitive and craft-like process of working with egg tempera merges my interest in both contemplative practice and manual labor. Its materiality helps to ground even the most conceptual or cerebral work in the bodily experiences of touch and craft. I was introduced to it by Tim Lowly, who was working a lot in egg tempera in the ‘90’s when I first met him. I was very interested in its optical and physical qualities: its relatively cool and light color tonality, matte surface, and the way that the tempera is applied with hatch marks that create a dense network of marks over the surface of the painting. Because it dries quickly and is very liquid, the paint is traditionally applied with pointed round brushes, and the process results in this richly cross-hatched surface that gives paintings a strong tactile presence. Tim introduced me to the work of George Tooker, Jared French, and Paul Cadmus, and through them, I developed an interest in Piero della Francesca and other Renaissance artists who had been their inspiration.

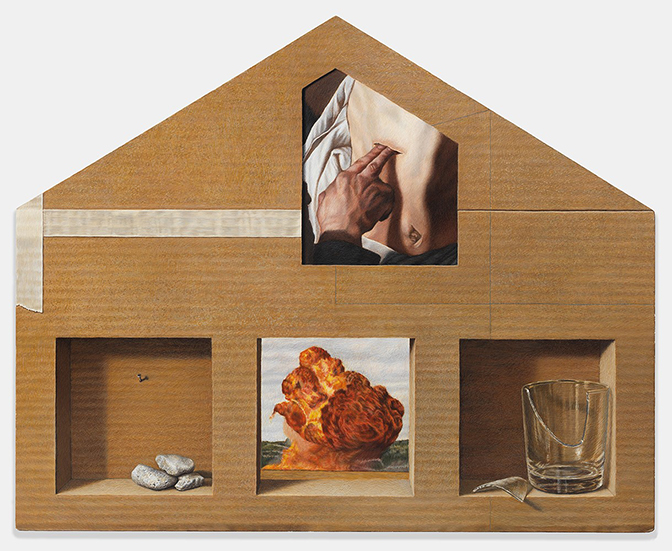

egg tempera on panel, 12 ¼” x 8 ¼”

Optics and the various physical properties of seeing appear to be a regular area of research for you. In conversation you noted The Ambassadors, 1533, by Hans Holbien the Younger. This painting is full of symbolism, but also is meant to be viewed from varied perspectives. Do you see parallels in approach or physical modes in seeing?

I do. Holbein’s painting is, on the one hand, a tour de force of realistic representation. On the other hand, there’s this intentional fracture in its visual language, which acknowledges the limitations of any representational language. I value that level of self-awareness in a painting, and I try to make my own work explore this complexity in our visual experience. As painters, we use a visual language that seduces and convinces us, yet we bump up against its limitations all the time. I think that a lot of the most interesting painting explores those limitations – those cracks in our perception and our visual language.

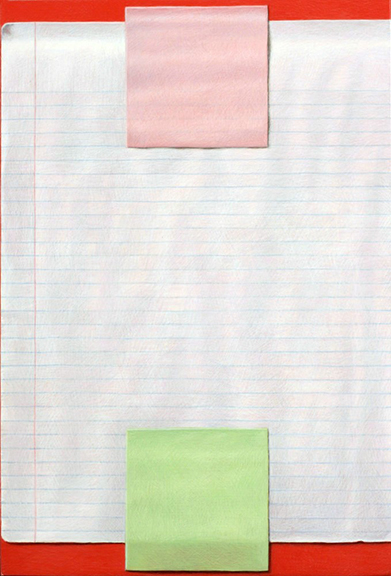

egg tempera on panel, 33” x 18”

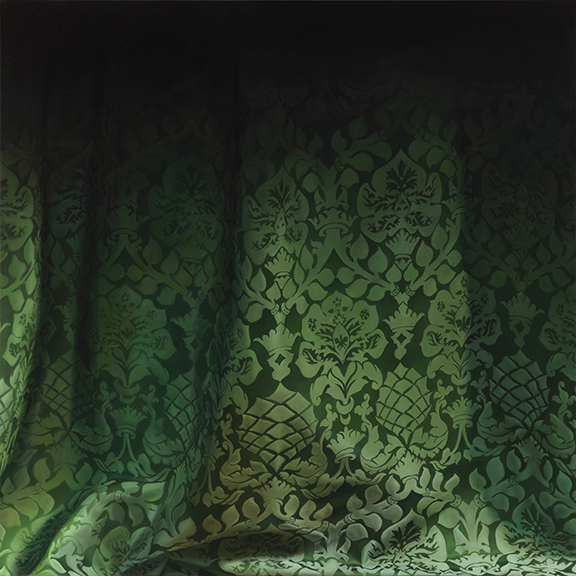

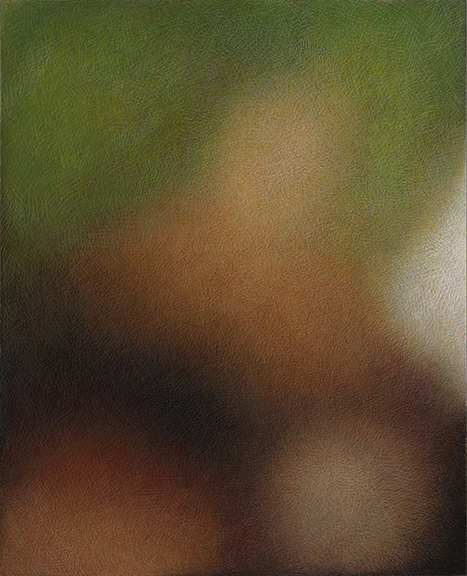

Your early work is hyperrealist. The series Observing Silence (1994-2004) are technically astute and precise. In recent work, for instance in the painting Profane Mimesis II, 2019, oil on linen, 60”x60”, there is the preciseness, but I also see a fall-off or blurring in some areas. Can you discuss how you see the evolution of your painting practice?

There are aspects of both continuity and change in that evolution. When I first started making realist paintings, I was very interested in the idea that close observation could be a form of contemplative practice. I tended to depict really ordinary subjects – a leaf or a rock, for example – isolated in a shallow space as if it were an object that demanded all of our attention. I wanted the paintings to pose the questions, “What is worthy of our attention? What is worthy of being depicted?” The frontal trompe-l’oeil format with objects depicted life-size was interesting to me, because it resulted in a painting that played with the distinction between image and object. The paintings were illusionistic depictions, but they often were initially received as collaged reliefs made of cardboard and tape. Over time, my trust in seeing became more complex – more aware of the limits of my own observation, and I became more interested in the ways our eyes lie to us; but that play between illusion and object – the depicted space of the illusion and the literal surface of the painting – turned out to be the perfect language for addressing such experience. My current work is still making reference to that visual language of trompe-l’oeil, but now I tend to create an illusion somewhere in the painting and then intentionally thwart it somewhere else, or I make a meticulously observed image of something that looks like an abstraction painted entirely from imagination.

In addition to your studio practice, you have taught studio arts (figure drawing, painting, etc.) for some time. Are there any items you attempt to regularly share with your students?

I have a few recurring themes in my teaching. I tend to emphasize the importance of attention. I feel that every artist needs to cultivate a practice of attentive seeing. Receptive observation is applicable to any visual language or medium, and it allows us to learn from our eyes. I’m not referring to realistic painting per se, and some of the most attentive observers I know are abstractionists, like the sculptor Richard Rezac and the installation artist Paola Cabal. The other leitmotiv that runs through a lot of my teaching is an emphasis on engagement with material. I encourage students to subject the objects they create to an intense process of craft. It could be a traditional material or a non-traditional one, but I want students to learn the parameters and exigencies of that material and develop a means by which they engage with it deeply until the process gives it form.

What do you value most in your aesthetic practice?

I think that my values are very much the things that I teach: the complexity of seeing and the contemplative nature of craft. The making of work challenges me to see more deeply and more subtly the longer I do it. At the same time, there’s still this blue-collar quality of work that making physical stuff keeps me engaged with. I find a lot of satisfaction in the process of refining a mark or a surface until the form really sings. Both of my parents were craftspeople who learned their crafts as apprentices: my mother a dressmaker, and my father a shoemaker. I think that there is something of their way of relating to the physical world in my relationship to painting and drawing.

Can you summarize what you are currently working upon? Do you have any upcoming exhibitions? What are your thoughts (or goals) about 2023?

I am working on expanding this series of paintings, titled Profane Mimesis, based on Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors, and on developing a new and related series, titled The Eye and the Hand. This latter is about relating sight to touch, and it derives from a series of Baroque paintings depicting the Incredulity of Saint Thomas. As the source images might suggest, these paintings also relate the senses of touch and sight to ideas of belief and doubt, which is on my mind a lot lately.

I have just committed to showing three of the Profane Mimesis paintings at Claire Carino Gallery in Boston this spring. I’ll also be participating in a group show here in Chicago at Color Club. The show at Color Club is curated by Andrew Falkowski and is titled Milk and Eggs. It is a show of contemporary paintings that make unconventional use of casein and egg tempera, and I’m really excited about that. Andrew is an exceptionally astute painter and observer of paintings, and I think he’s putting together a show that will be engaging both conceptually and sensuously.

I’m also always writing grant proposals and project proposals, trying to generate opportunities for new work. The gallery that used to represent me in Chicago closed in February of last year, so one of my goals is to find new gallery representation here in Chicago and possibly elsewhere.

For additional information on the studio practice of Steven Carrelli, please visit:

Steven Carrelli – http://www.stevencarrelli.com/

Hofheimer Gallery – https://hofheimergallery.com/artists/steven-carrelli/

Steven on Instagram – https://www.instagram.com/stevencarrellipittore/?hl=en

New American Paintings – https://www.newamericanpaintings.com/artists/steven-carrelli

Addington Gallery – https://danaddington.com/addingtongallery/carrelli/carrelli.html

Artist interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello