Having photographed in an array of places, including Chicago public housing, the New Deal “Greenbelt Towns,” the Philippines, and central Illinois, one can see how Jason Reblando’s aesthetic practice is actively influenced by his background in sociology in a manner that recalls prominent social documentarians who worked in the early 20th century. In 2017, Reblando published New Deal Utopias. This thoughtful photobook examines the Greenbelt Towns that were built as ideal cities during the New Deal in the 1930s. This week the COMP Magazine caught up with Reblando to discuss his new book, how place impacts his photographic practice, his documenting of the Filipino diaspora, the cultural significance of the balikbayan box, and his role as an educator.

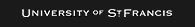

Jason Reblando, New Deal Utopias, Kehrer Heidelberg Berlin, 2017

After becoming familiar with your work over time by way of our virtual world, I find it interesting that we finally connected through the release of your book, New Deal Utopias, 2017, at the MoCP’s book signing event. Can we backpedal a bit? Your parents are Filipino immigrants; you grew up out east, studied in Boston, then Chicago, and now teach in Bloomington-Normal in central Illinois. On one level I clearly see your early studies in sociology influencing your approach to photography. I’m curious if you can share with us what prompted your current efforts? Are there any individuals or works that you see as informing your practice?

Thanks for mentioning my undergraduate degree in sociology. I think my interest in society and power structures certainly informs my photographic practice. I think it might be worth mentioning that it did take me awhile to consider photography as my vocation. There was a thirteen year gap between receiving my bachelor’s degree and pursuing my MFA. While my background in sociology was important, my work as a community organizer in southern Oregon as a member of the Jesuit Volunteer Corps was a formative experience for me. One of my jobs was canvassing door-to-door to protect public health services in the county by raising the tax base that hadn’t changed for twenty years. I knocked on a lot of doors of people who depended on public health clinics. I also met people who didn’t think their taxes should fund public services. While I got a fair share of doors slammed in my face, I became aware of the complexities of these issues by listening to people’s stories. After each interaction, I came away with more questions than answers. I think this constant curiosity about a particular topic or issue has allowed me to make images that can be nuanced and open-ended, leaving room for viewers to be curious themselves.

There are so many things that inspire me – friends, colleagues, students, books, magazines, websites – but I think my professors in graduate school at Columbia College and working at the Museum of Contemporary Photography exposed me to a lot of amazing material and art that I hadn’t been exposed to before. Coming from a social science background, my MFA was a real crash course on contemporary practices and art theory. These experiences and interactions have continued to influence me, socially, academically, and professionally, as far as showing me the importance of having a creative community that I can trust.

One recent thing that I think will influence my practice was co-chairing the Midwest Society for Photographic Education Conference with Margaret LeJeune in Peoria this past fall. We organized the conference around the theme of Developing Spaces/Places, and hosted an amazing roster of speakers, exhibitions, workshops, and of course, our dedicated members. It was inspiring to see so much great work and hear ideas from artists throughout the Midwest and beyond.

Jason Reblando, Isaiah and his cameraphone, Stateway Gardens, Chicago, 2006.

In looking at your various projects (e.g., Lathrop Homes, Outside Public Housing) I see an attention given to place and how it influences one’s life. Since you have lived and worked in a number of cities, I am wondering how the environment in which you have worked has influenced your working method?

I think my interests in photography, urban planning, architecture, and social issues all feed off of each other, and having access to a city such as Chicago is an amazing privilege to explore these interests via a number of different approaches.

However, my experiences living away from Chicago have been as important, if not more important, regarding my need to adapt my artistic practice. I was fortunate to receive a Fulbright fellowship to the Philippines, and I needed to establish new relationships with people in order to work on a project on families of Overseas Filipino Workers. I didn’t have the luxury of the ability to go back to the same public housing project every week for two years and develop long-term relationships with residents as I had done with Lathrop Homes during graduate school in Chicago. My work in the Philippines required a ton of planning and flexibility. In this project on the Filipino diaspora, I’m examining the meaning of place and home to a population that is largely absent, as ten percent of the population of the Philippines is working abroad and sending money back home. This contribution to the global workforce provides economic benefits to the country and families, but has social ramifications as well. Throughout my projects I enjoy using the concept of place as a point of entry that can lead to other research interests, such as migration, architecture, identity, and labor.

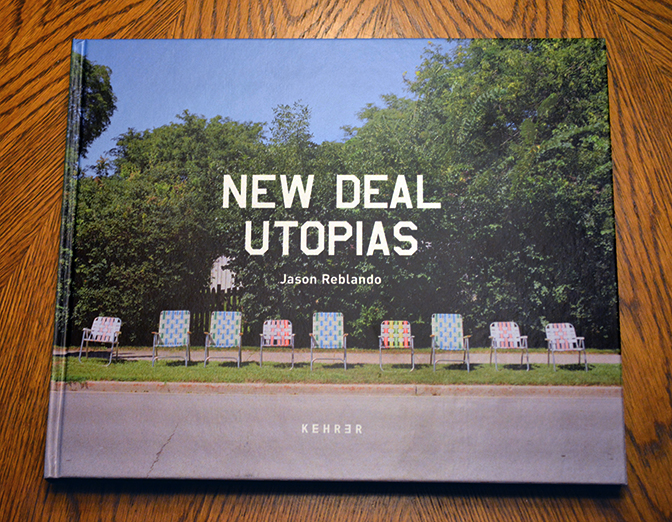

Jason Reblando, New walkway at former site of Cabrini-Green, Chicago, 2010.

Jason Reblando, Phil Johnston, Brickwasher at new buildings on former site of Cabrini-Green, Chicago, 2002.

Lets discuss New Deal Utopias, published by Kehrer Verlag Heidelberg, 2017. Can you summarize your progression in this project and how you came to the point where you decided to publish this in book form? What did you find most rewarding in this process?

There’s a somewhat circuitous through-line, but things are indeed connected. While I was photographing at Lathrop Homes in Chicago, I learned that it was atypical public housing stock. It is a complex of red brick row houses and 3-4 story walk-ups located on the North Side of Chicago along the banks of the Chicago River. When photographing Lathrop Homes, I wanted to humanize the buildings that were often discounted as hollowed out and decrepit. I wanted to emphasize that a community of residents not only lived there, but also had emotional ties to Lathrop. I was struck by its verdant courtyards and architectural character, and learned that it was built by the PWA during the Great Depression. I also learned that Lathrop Homes was built with “Garden City” principles in mind, a set of principles put forth by Sir Ebenezer Howard, an late 19th-century English urban reformer who was appalled by the overcrowded slums of London. Howard proposed decentralizing urban areas and building new communities that combined the best of the “town” and best of the “country,” namely the social and economic advantages of living in a community with the fresh air and open green spaces of nature.

Jason Reblando, Krystal, Lathrop Homes, Chicago, 2007.

I learned that Franklin Roosevelt’s short-lived New Deal agency, the Resettlement Administration (RA), constructed three pilot communities around the same time that Lathrop was built. They, too, were all built with in the style of Garden Cities, but the RA designated these three towns as “Greenbelt Towns” – Greenbelt, Maryland; Greenhills, Ohio; and Greendale, Wisconsin. These “Greenbelt Towns” embodied the hope that American citizens would meet the challenges of the Depression in a spirit of cooperation, not individualism. They raised suspicions of socialist towns in America, but have become an indispensable prototype for urban planners around the world. The more I read about their history, the more I wanted to see them for myself. I decided to zoom out geographically and conceptually and visit each of the towns.

Jason Reblando, Daffodil House, Greendale, Wisconsin, 2009.

Jason Reblando, Gazebo, Greendale, Wisconsin, 2009.

While making the photos for New Deal Utopias, I had Howard’s Garden City in mind, and focused on the built and natural environments. I wanted to depict the communities as pristine models. While the scenes are largely vacant, the buildings and landscapes are laden with human experience, attempting to evoke the egalitarian and cooperative vision the planners envisioned.

I also found it fascinating that the administrator of the RA, Rexford G. Tugwell, had hired Roy Stryker to head up the Historical Section of the RA, to document the economic woes of the Great Depression. The RA would eventually become the Farm Security Administration, the agency that photographers are more familiar with.

Regarding my decision to pursue publishing a book, I’ve always had publishing a book as a professional goal. I fell in love with photography books through a documentary photography class with Bob Thall at Columbia College. I enjoyed editing, sequencing, and designing our final projects that would become self-published books. I thought that my New Deal Utopias project could be a possible book because of its unique historical component and broad-reaching subject matter of utopia and the built environment. I couldn’t be happier that Kehrer Verlag published New Deal Utopias and I’m very excited to be part of their amazing catalog of books.

Publishing a book has been challenging and rewarding at every stage of the process. It’s more work than I ever imagined, and I hope I have the opportunity to do it again. I loved working with a team of people who contributed their expertise to and believed in my project, from the essay contributors Natasha Egan and Robert Leighninger to the book designer Jason Pickleman to the team at Kehrer that patiently guided me through every step of the process. Overseeing the printing of the book on a Heidelberg press in Germany was particularly thrilling and enlightening. It was humbling to realize how many hands the project passes through for the book to become a physical object that someone can enjoy. I’ll never look at books in the same way again.

Jason Reblando, Mural, Greenhills, Ohio, 2009.

You recently published a piece on the Filipino Diaspora in the Atlantic’s CityLab. Some of this work was made in Joliet, Illinois. Many are unfamiliar with what a balikbayan box is. In the piece you have a conversation with a patient relative who notes, “that balik means return and bayan means home”. Can you offer insight into the cultural significance of the balikbayan box? What do you hope to convey in this project?

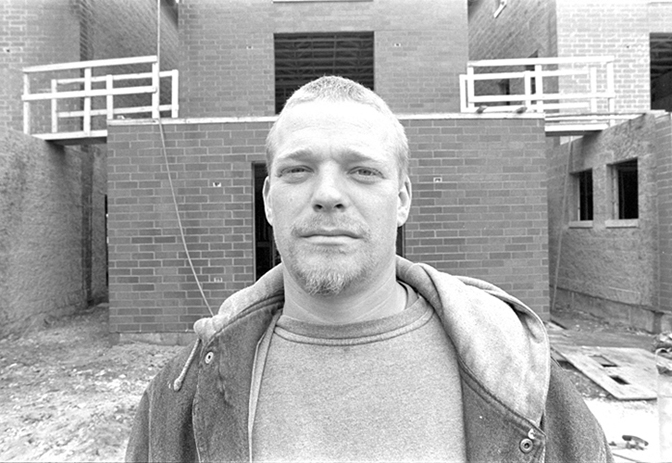

Absolutely. A balikbayan box is a large cardboard box that Filipino families around the world use to ship items back home to relatives in the Philippines. These boxes were a constant presence in my parents’ garage and living room on Long Island where I grew up. They were sending clothes, tins of cookies, toys, and other non-perishable items to family back in the Philippines. Only as an adult did I realize that these boxes were being sent to the Philippines from every part of the world. Further, I’m discovering I’m only now becoming more aware of the reach and importance of the Filipino diaspora and the role that Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) play in the world economy. They leave their families to work as pipe fitters in Russia, domestic workers in Hong Kong, restaurant servers in Dubai, nurses in Canada, engineers on tankers. When my relative explained to me that in Tagalog, “balik” meant “return” and “bayan” can mean “home” or “town” or “nation” I realized that the term “balikbayan” can refer to the box that is returning home, but the term can be used for the person who is sending the box.

Also, I should mention that nothing urgent should be sent in a balikbayan box. While $60 is relatively inexpensive to send a 24″ x 17″ x 19″ box halfway across the world, the trade-off is that it often takes two months, door-to-door, for the package to arrive in the Philippines.

Jason Reblando, Mulanay vanity license plate, Joliet, Illinois, 2014.

Jason Reblando, T-Bar International employee, Quezon City, 2015.

For me, the balikbayan box and its contents symbolize the sacrifice that OFWs make when they decide to leave their family for years, sometimes decades, at a time, in order to support their family. From my own family’s experience and from what I’ve seen when working on this project, the items are usually not very exotic. Spam, cookies, perfumes, headphones, clothing, etc. The irony is that almost everything in the box can now be purchased in the Philippines. However, who doesn’t like opening a huge box full of gifts? It is almost solely based on sentiment. The balikbayan box is essentially a care package, but with one crucial difference. Care packages usually come from *home.* Balikbayan boxes come from *abroad* and get sent to the Philippines.

With these images, I not only hope to evoke the absence of family members who are toiling away in foreign lands, but also to highlight the middlemen who make these tangible long-distance connections possible. It’s essential that families receive money wired from abroad, but receiving a box of goodies from loved ones overseas might be the next best thing to being there. Balikbayan delivery services make this happen.

Jason Reblando, Colgate from Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2017.

What do you value most in the making of pictures?

I love the challenge of noticing something that could carry meaning beyond the scene or object itself. I also value the act of researching a topic. I used to work in lung cancer research after college, and my former boss told me that in order to discover anything new, we need to dig a mile deep and an inch wide, not a mile wide and an inch deep.

As an educator what do you see as your role in assisting your students in their growth as artists? Are there any ideas or items you routinely share with your students?

I currently teach at a community college, a private liberal arts college, and a state university. Every student comes in with different levels of experience and different expectations of what they think photography is since everyone has already taken thousands of pictures with their cell phones or entry-level DSLRs. It’s a challenging but exciting time to teach photography since most students are so used to immediate feedback when they post photos on social media. As an educator I think my role is to teach them how to be visually literate and be critical thinkers of photography in the 21st century. It’s rewarding to teach them technical skills in whatever class I’m teaching, but I also enjoy assisting them in understanding that photography is a visual language, and they could and should use photography to create conceptual meaning.

Something that I routinely share with my students is a box of prints that I made for my series on youth boxers in Chicago. The project spanned over four or five years, but more importantly it spanned over five photography classes. I show these prints when I introduce final projects and inform them that they will need to return to the same topic over the last 6 weeks of class and edit, rework, and build on the images from work-in-progress critiques. I then show them how my project on youth boxers evolved as I applied skills learned from a black-and-white class, a color class, a portrait class, a lighting class, and a digital printing class. I think it’s essential for students to see that our projects and ideas are never static and always developing.

Having recently completed New Deal Utopias, what’s the next step in your investigations? What are you currently working upon? Do you have any specific plans for 2018?

I want to continue to explore various aspects of the Filipino diaspora in different parts of the world. I began some work with Filipino communities in Europe and the Middle East last spring and am still working through these images. This will be an ongoing project while I continue to promote New Deal Utopias through exhibitions and book talks.

My specific plans for 2018? Backup my hard drives. Finally!

For additional information on the photography and projects of Jason Reblando, please visit:

Jason Reblando – http://www.jasonreblando.com/

Marketplace – https://www.marketplace.org/2017/08/18/economy/greenbelt-maryland-cant-hide-its-town-pride

Museum of Contemporary Photography Chicago – http://www.mocp.org/collection/mpp/reblando_jason.php

New Deal Utopias – https://www.amazon.com/New-Deal-Utopias-Jason-Reblando/dp/3868287906

Upcoming talks:

February 22, 2018 – MAS Context Spring Talks series at the Society of Architectural Historians, Charnley-Persky House, 1365 N. Astor Street, Chicago, IL 60610. – http://www.mascontext.com/tag/jason-reblando/

March 21, 2018 –Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, University of Michigan. Art and Architecture Building. – https://taubmancollege.umich.edu/events/2018/03/21/jason-reblando-architectural-photography

Artist interview by Chester Alamo-Costello